Rui Shi

“Hauntology is, for me, inseparable from queer experience in digital space.”

Rui Shi is a London-based artist whose work moves between digital worlds, sculpture and moving image, exploring queer identity, hauntology and the politics of virtual space. In this interview, Shi discusses how game environments shape our sense of self, the role of wandering and transformation in their films, and the collaborative myth-building they develop with artist Zijing Zhao.

Could you tell us a bit about yourself and your background?

I’m an artist from China, currently based in London. Trained in stage and spatial design, I started out building environments for magazines and sci-fi film productions, thinking about how images choreograph bodies in space. I later shifted into Fine Art at the Royal College of Art, and I’m now a practice-based PhD researcher at UAL, focusing on queer identity in digital space, especially within video game worlds. Alongside this, I develop sculptural and moving-image works that shuttle between virtual landscapes and physical matter.

Your films draw on digital worlds that feel both familiar and uncanny. How do you see your work reflecting or questioning our experience of living in an increasingly virtual age?

This question is very close to my current PhD research. I’m deeply influenced by Mark Fisher’s idea of hauntology: even though our world appears increasingly wrapped in technology and digital interfaces, the underlying images and narratives are still endlessly haunted by dominant cultural patterns. For me, digital space should hold the potential for radically different perspectives and bodies to appear, but in reality it’s heavily shaped and constrained by existing entertainment industries, especially mainstream gaming. That’s why my moving-image works often start from within those systems: I use screen recordings of popular video games, together with mods and in-game interventions, as my raw material. Hauntology is, for me, inseparable from queer experience in digital space. The figures that move through my works feel more like ghosts or glitches than stable characters.

They drift between virtual landscapes and physical reality, never fully at home in either. In that sense, the films are less about representing queer identity in a fixed way, and more about tracing these haunted, in-between states—how queer bodies navigate a culture that keeps “updating” its surface while repeating the same structures underneath.

You also collaborate with artist Zijing Zhao on a duo project called. Can you tell us about the project and how it connects to your individual practice?

During my two years at the RCA, Zijing and I became increasingly drawn to Asian mythologies and apocalyptic visual worlds. When the pandemic suddenly suspended the usual rhythm of life, we were confined at home and started to seriously explore how digital space could intersect with mythic and folk narratives. I became obsessed with end-of-the-world and sci-fi settings, and with building atmospheres through set and environment design, while Zijing has a very strong sense for myth-based and speculative storytelling. Together we turned to stop-motion animation as a way to make experimental films, using it to test out questions that still stay with us now, from links between gender identity and East Asian myth, to monstrous female bodies, to worlds that are constantly mutating and evolving. These early projects really shaped how I work today: they taught me to treat sculpture as a kind of world-building and to use moving image as a space where myths, bodies and environments can keep being rewritten.

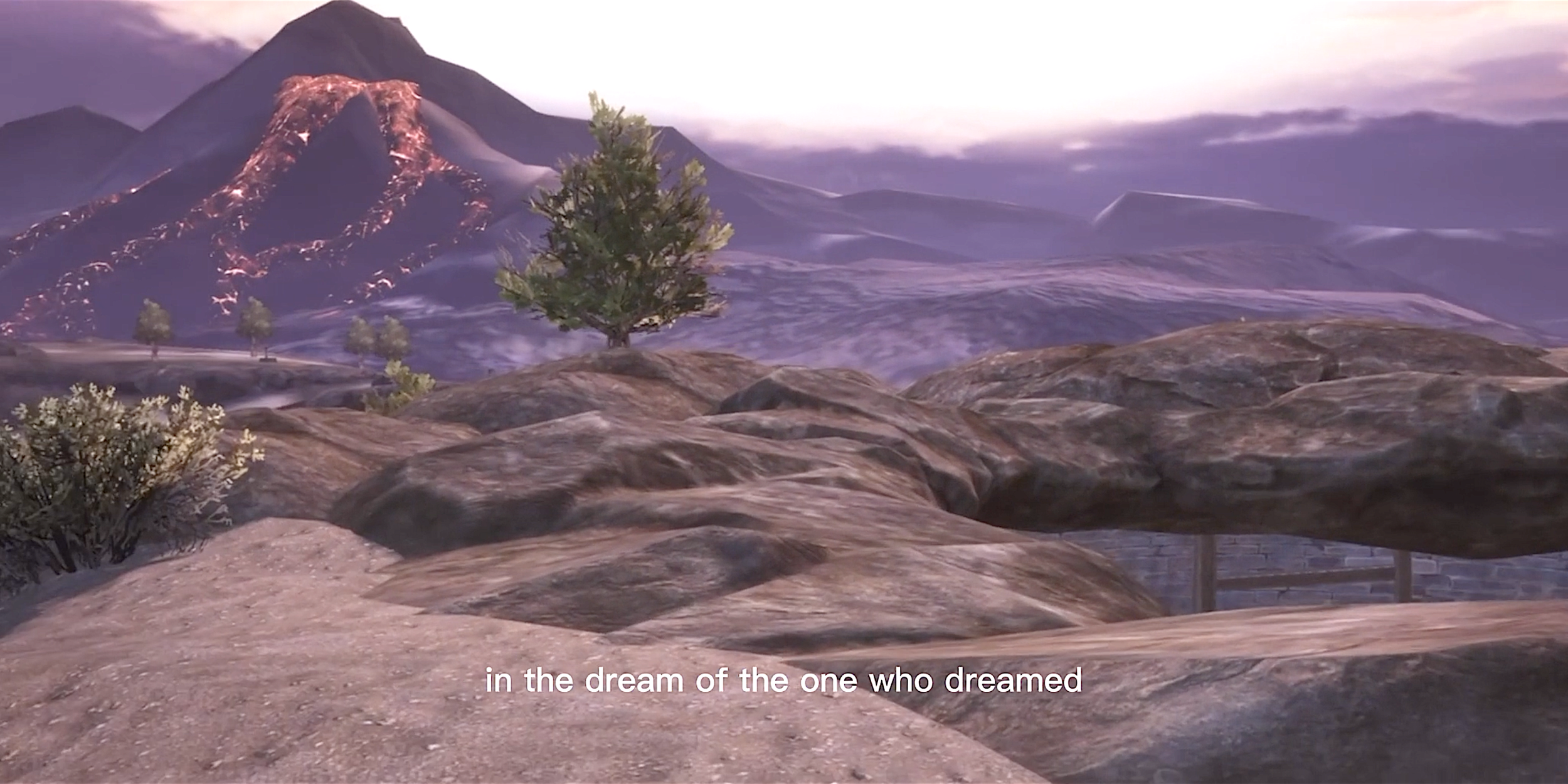

Ghost Through the Looking Glass, 2024

Ghost Through the Looking Glass, 2024 (still)

Ghost Through the Looking Glass, 2024

Across your practice, there’s a feeling of characters searching or wandering through fragmented landscapes. What interests you about using the moving image as a way to explore identity and transformation?

For me, these “wandering characters” are a very honest image of a queer state of being. Whether they appear as humanoid figures, monsters or partial, broken bodies, they are always in a kind of loading phase: no longer who they were, but not yet who they might become. Moving image is naturally suited to this sense of incompleteness. Time can be stretched, paused, looped, and identity stops being a fixed outcome and becomes a sequence of small attempts, glitches, failures and reboots. I am also very interested in the idea of getting lost. When characters drift through fragmented landscapes, they are not just lost in space; they are testing different paths, different bodies, different ways of existing. Working with moving image allows me to layer multiple spaces and perspectives at once, so these figures can keep switching skins, becoming plants, wormholes, interfaces or weapons. Through this constant wandering, I want to suggest that identity is not a stable point waiting to be discovered on a map. It is more like an ongoing motion of adjustment, a process of tuning, mutating and rerouting yourself in response to the worlds you move through, both digital and physical.

Tell us a bit about how you spend your day / studio routine? What is your studio like?

On most days I start by going to the boxing gym. That bit of training puts my body under pressure in a good way, and my mind drops into a kind of meditative focus. After that I have breakfast with Zijing and we head to the studio together. My studio is full of plaster and stone pieces. I usually put on a playlist I love and begin carving. The repetitive, physical rhythm of carving is very calming for me, almost like a grounding ritual. Throughout the day I move back and forth between different activities in the studio: playing video games, watching moving-image works, editing footage and making small sketches. Shifting between these modes keeps the work alive, and the games and images often slip back into the sculptures and films in unexpected ways.

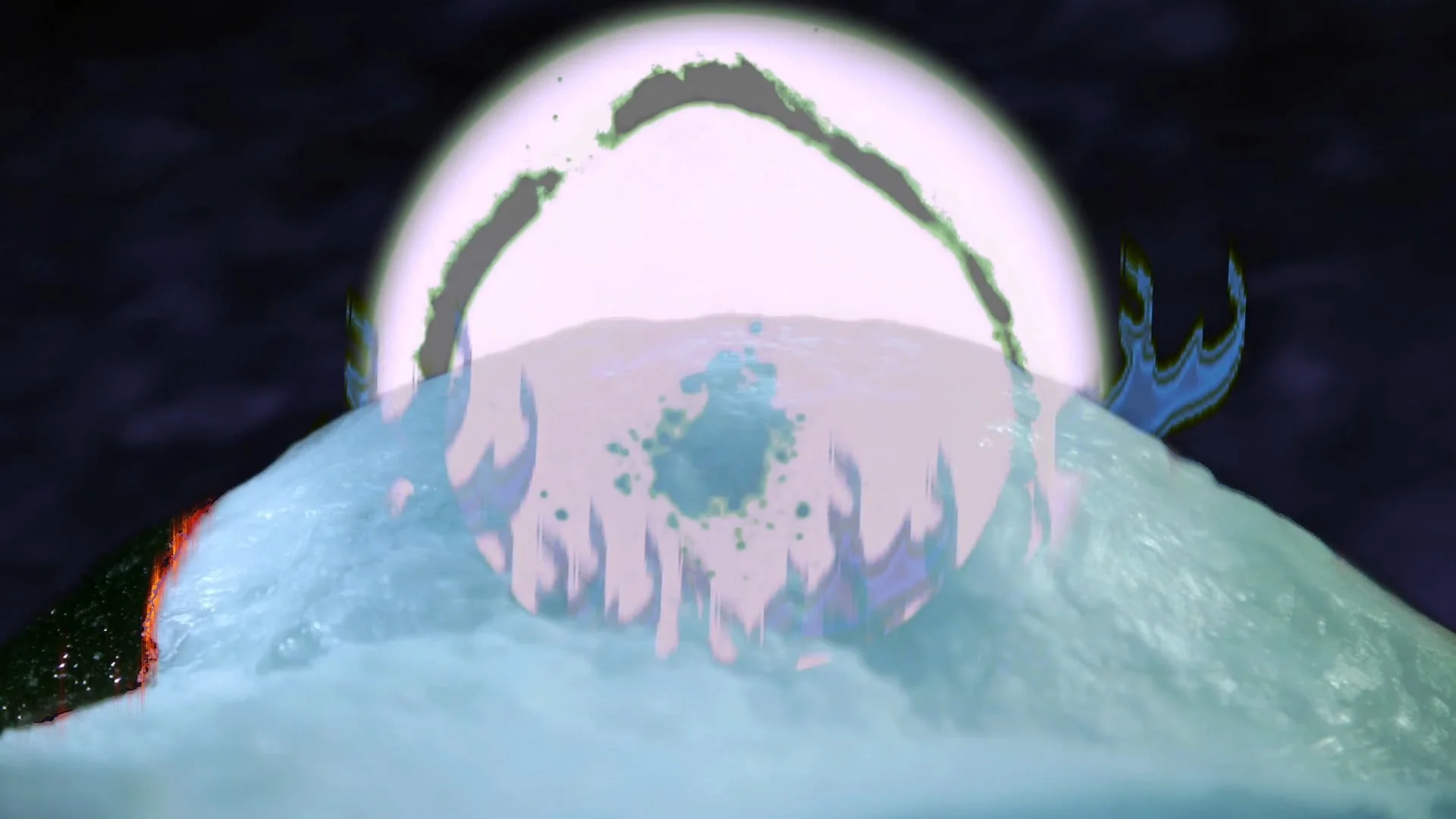

Phantoms, 2023

Mountain of Flames, 2020

What artwork have you seen recently that has resonated with you?

Recently I was really struck by Ed Atkins’ exhibition at Tate Britain. The way he works with text, voice and digital bodies creates a space that feels at once intensely intimate and strangely disembodied, which speaks very directly to my own questions about how we “live inside images” today. The way vulnerability, failure and repetition play out again and again through these constructed virtual figures has stayed with me, and it continues to shape how I think about narrative and the digital body in my own work.

Is there anything new and exciting in the pipeline you would like to tell us about?

I’m currently working with Zijing on a new exhibition titled Every Video Game Depicts an Apocalypse, which will be shown in London early next year. The project brings together multi-channel moving image, sculpture and interactive digital landscapes, and continues our ongoing research into queer ecologies and the construction of monstrous worlds.

All images courtesy of the artist

Interview publish date: 20/11/2025

Interview by Richard Starbuck