Ciana Taylor

“Using character allows me to create distance; it acts as a lens that reveals belief systems and behaviours that once felt completely normal but now appear strange or unsettling.”

Ciana Taylor is a London-based Irish artist whose moving-image practice blends archival research, performance, and installation to explore belief systems, cultural memory, and the lingering influence of Ireland’s religious past. In this interview, Taylor discusses how character, tension, and atmosphere shape her work, and how she builds immersive environments that draw viewers into questions of identity, history, and contemporary ritual.

Could you tell us a bit about yourself and your background?

I’m an Irish artist, born in Dublin but raised in Bahrain before returning to Ireland at thirteen. Ireland itself plays a huge role in my practice; it's a place that is so joyful yet shadowed by its history, so progressive yet deeply traditional. That duality is something I return to again and again. Like most artists, making has always been a refuge for me. I didn’t fully recognise that until after school, when I was working as a waitress and pursuing acting. I really felt the loss of my weekly art classes and realised that taking time to think and make was something I needed to do regularly. So I stopped acting, started painting again and eventually went on to study Fine Art at Chelsea College of Art, London. Art school was liberating - it gave me permission to experiment and be a bit weird. I started writing more, making films on my iPhone and soundscapes on GarageBand. I loved how all the elements began to converse with each other and developed a rhythm. I got really into video art by artists like Laurie Anderson, John Smith, Patrick Goddard and Johan Grimonprez, and into the research process itself: immersing myself in a subject and letting it guide my life for a little while. The films became a kind of diary - a collaboration between the subject matter, my lived experience, and the threads that connect the two.

Your practice often transforms archival research into deeply atmospheric works. How do you approach translating historical material into moving images or installations that feel emotionally charged and contemporary?

It’s a very intuitive process for me. I do a lot of digging, and when I find something that resonates, I just know. It feels exciting. There’s usually something subliminal in it - a small gesture, a tone, or a detail that feels like a clue, something that helps me understand what I’m investigating a little better. I collect these fragments, and when I start putting them together, a flow emerges. I usually lead the editing with a soundscape. The feeling translates through that process; it becomes a form of communication, almost like passing a baton from one person to another. I think what makes the work feel contemporary is that it’s innately experimental. I don't really follow any traditional rules or structure while I’m making. I’m not trying to recreate the past objectively; I’m reinterpreting what I find, what resonates with me, and recontextualising it in ways that speak to the present - it’s fuelled by my own experiences and relationships. I think when you lead with that, people can feel it.

Sex Education for Girls, 2023

Confession Booth, 2024, Captured by Ben Deakin

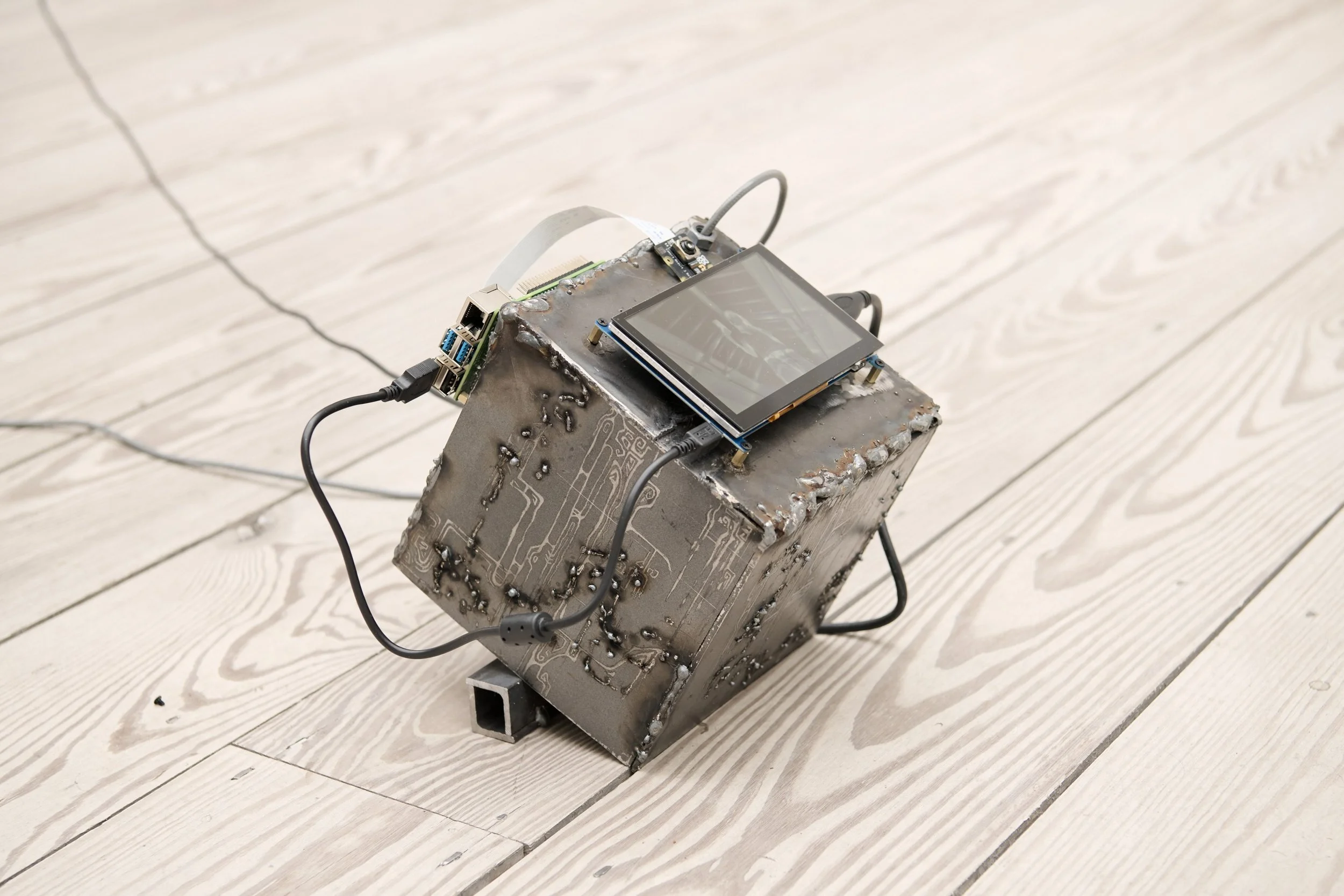

On Data as Dust, 2025, made collaboratively with Jamie Seechurn (@Thameswater), Captured by Benjamin Werner

Interstice, 2025, made collaboratively with Jamie Seechurn (@Thameswater), Captured by Benjamin Werner

Your films touch on the legacy of the Catholic Church and its impact on women in Ireland. What do you want audiences to sense or question when they encounter these themes through your use of character and performance?

I want audiences to experience a sense of tension. Using character allows me to create distance; it acts as a lens that reveals belief systems and behaviours that once felt completely normal but now appear strange or unsettling. By embodying something from that time, I can hold it up for examination - creating a space where viewers can reflect on how a completely different ‘normal’ existed not long ago, how it shaped lives in ways that are still relevant today, and how unstable our current normal really is. In my piece Sex Education for Girls, ‘Angela’ is gentle, yet her attitude toward sex is puritanical and awkward. I want to confront people with that, to encourage them to question their own experiences and assumptions. Our sense of morality and opinions are shaped by the systems we grow up in, and it’s important to consider who we might be - or what we might believe - if we had been formed by different circumstances. When I work with performers, it’s about exploring that complexity: examining my own perceptions of right and wrong, and inviting audiences to do the same.

The presentation of your work combines sculpture, sound, and multi-screen projection, creating a space that feels part cinema, part ritual. How do you think about installation as a way to shape how viewers physically and emotionally experience your works?

I went to church a lot as a child and was actually quite religious. I loved the cinema too; both were quite formative for me. In a way, the church and the cinema share a similar function: they both ask you to suspend disbelief and give yourself over to an experience. Installation asks the same thing, and it can achieve that same sense of collective focus and awe. It’s a visceral language: your whole body has to enter the space to experience it fully. The space itself becomes the work - sound, visuals, and objects combine to create a particular feeling - a bit like a church, or a cinema. I think a lot about rhythm, creating a push and pull between familiarity and obscurity. I want the films to exist in conversation with their surrounding environments, inviting people to feel into the experience, make their own connections, and draw their own conclusions.

The Old 9-5, 2025

The Homes We Build, Still, 2025

Tell us a bit about how you spend your day / studio routine? What is your studio like?

My flatmate and I have converted the living room into a combined living and studio space, so I guess I live in my studio. It’s been working really well - I can roll out of bed and get straight to work. Mornings are when I feel sharpest and most creative, so this setup stops my head from getting muddied by a commute. I usually start the day writing, which helps me keep track of my dreams and check in with where I am creatively. That, in turn, guides my ideas for the day. My routine is a mix of structure and wandering. I make a list of things to focus on, then sit and work for as long as I can, whether that's with clay, paint, or editing. At some point, I'll take a walk, film, and let ideas come naturally. I walk a lot, and bring my camera with me when I can. Sometimes I'll work from the British Library, which is a great environment for researching, planning, or editing. If I need to work with metal or do some casting, I go to the London Sculpture Workshop.

What artwork have you seen recently that has resonated with you?

I recently watched A Want in Her by Myrid Carten at the Irish Film Institute, and it blew me away. I thought it was incredible. The film follows Nuala Carten, an addict and Myrid’s mother, who goes missing somewhere in Ireland. It blends home‑movie footage, phone recordings, performative sequences of Nuala directed by Myrid, and a thorough visual investigation of Myrid’s surroundings in Donegal. Myrid clearly adores her mother, but you can see that the relationship is strained. Nuala is complex - she’s difficult, but she’s very likeable. At its core, I think it’s about trying to love someone without losing yourself. It captures the duality of Irishness that I mentioned earlier very well, too. I’d consider the film more an artwork than a traditional documentary; you can really see Myrid’s background as a visual artist. I relate a lot to her process - collecting footage and reflecting on family archives. It’s definitely had a big influence on the work I’m doing at the moment, and I guess reaffirmed my attitude towards making.

Is there anything new and exciting in the pipeline you would like to tell us about?

I’m currently working on my largest body of work to date, an ongoing project exploring faith, identity, and Irish culture. I’ve just spent a month in Ireland filming and interviewing women about their experiences of the country’s recent shift toward secularism. The project has since expanded to include queer voices, members of alternative religious sects, and born-again Catholics. I’ve been collaborating with my friend Molly Mew - who I worked with on Sex Ed - to create visuals inspired by these conversations. Alongside this, I’ve been collecting footage across the Irish landscape and in domestic spaces, and working with musicians to make soundscapes from the material I’ve gathered. I’ve also been experimenting with sculpture and using new materials, so the project is evolving across multiple forms. The work asks what forms of spirituality emerge when traditional religion dissolves, tracing how Irish identity continues to negotiate its spiritual inheritance - the echoes of Catholicism, folk mysticism, and the personal mythologies that arise in their absence. It contemplates how we construct our own cathedrals from fragments of culture, history, and home.

All images courtesy of the artist

Interview publish date: 20/11/2025

Interview by Richard Starbuck