Henry Curchod

“In my recent work there is no real construction of an image happening; but more a construction of a timeline. It seems that one of the key pillars of good painting is an artist’s confidence in their ability to ‘change their mind.’ “

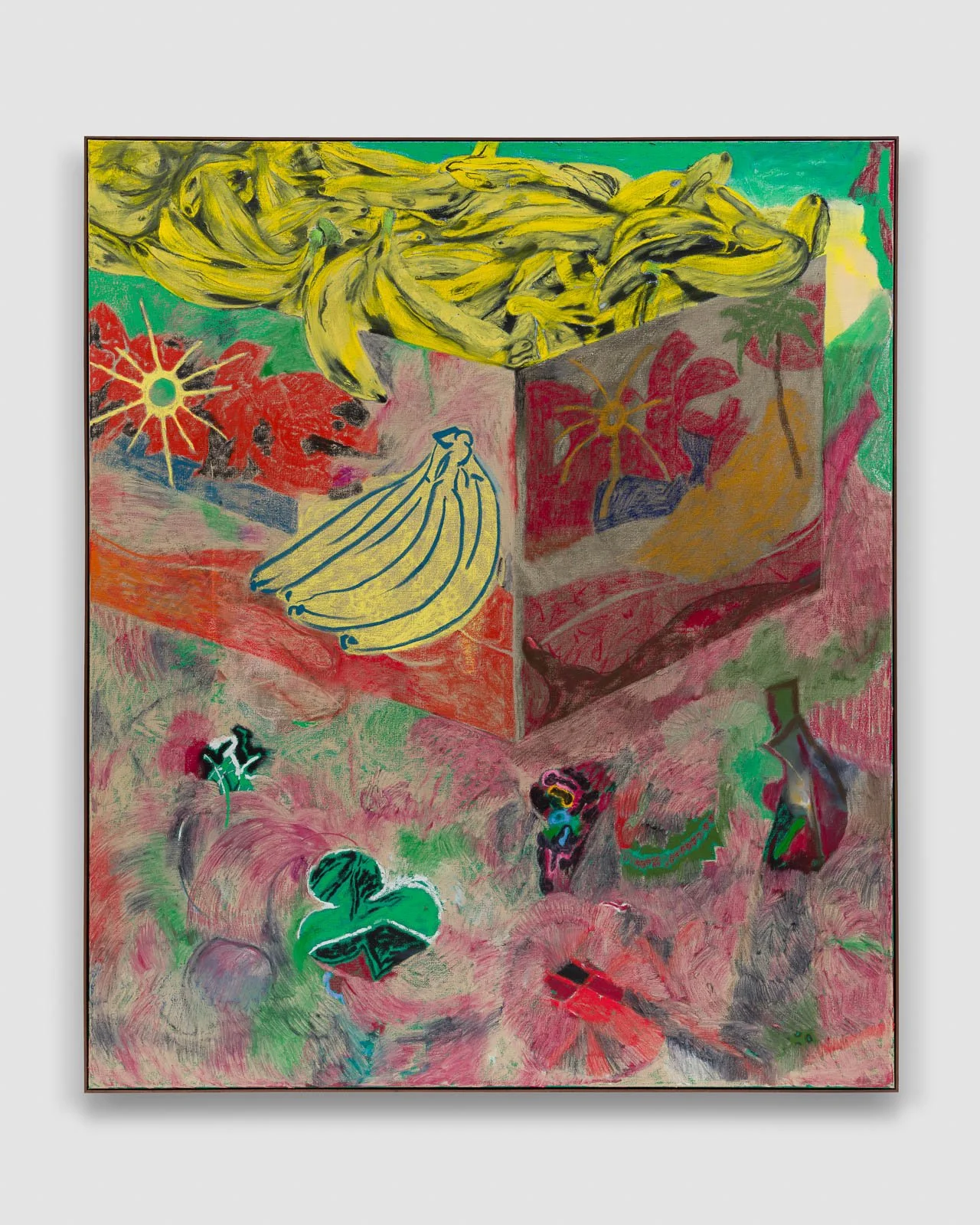

Henry Curchod is a London-based artist whose work explores themes of identity, hybridity, and process through painting, drawing, and textile-based forms. In this interview, he reflects on the cultural influences that shape his practice, the physical and emotional demands of image-making, and the ideas behind his latest exhibition Rome is no longer in Rome at C L E A R I N G Los Angeles.

Could you tell us a bit about yourself and your background?

Its a bit complicated — my father is Iranian (Kurdish and Persian depending on the context of the question), he was born in Baghdad, but grew up in Iran and sent to California as a teenager just before the Islamic Revolution, where he met my mother who is of European descent but spent most of her life between California and Sydney. I don’t really consider myself to belong to any specific community, and whilst I now live and work in London, I would call Sydney ‘home’.

Your new show at C L E A R I N G in Los Angeles is titled ‘Rome is no longer in Rome’ — can you start by telling us about the title and where these paintings were made?

The show was made one painting at a time over a four month period in my studio in Hackney. I was supposed to read Edouard Glissant’s ‘Poetics of Relation’ in art school, but only actually picked it up at the beginning of the year at the recommendation of a friend, who noted that I was talking about some of the themes in there and needed more structure to my thinking. Inside of this masterpiece, is that quote, which was originally attributed to the playwright Pierre Corneille in the 16th century. It has many possible interpretations — but in the context of my life and my work, it illustrates that our identities are shaped by the complexities of our interpersonal relationships, and not strictly the places we are ‘from’. This led to a deeper understanding of hybridity and how that might manifest in art-making.

How does this idea of hybridity manifest in your practice?

Formally, I have always played in that space between drawing in painting — which I am now seeing as a sort of battle between the Eastern and Western corners of my ‘root system’ and upbringing. Drawing could be seen to represent the East and painting the West. The same could be said for the battle between abstraction and figuration in my work… If you’re inclined to look at things that way. And recently this has expanded onto different planes where I am painting/dying/drawing on blank rugs sent over from Tehran and creating conversations between the floor and the wall; the X and Y axis, or East and West.

I find this most compelling when thinking about the differences in how the East and West tend to interact with art: paintings on the wall demand this kind of Western Art reverence, whereas in Eastern cultures it is traditionally more common to live, in, on, or around art. That is why I encourage people to walk on the painted rugs whilst they engage with the ‘drawn’ canvases.

C L E A R I N G, Los Angeles, May 31, 2025 - July 26, 2025

21.01.25 – 03.02.25, 2025

06.02.25 – 11.02.25, 2025

C L E A R I N G, Los Angeles, May 31, 2025 - July 26, 2025

Across these new works, there's a real feeling of motion, not just in the poses of the figures, but in the way the scenes seem to shift, fragment, or fold into each other. How do ideas of movement or dislocation influence the way you construct these images?

The movement is simply a product of the physicality and violence (for lack of a better word) that drawing at a large scale demands.

The fragmentation and shifting in these works might just be evidence of a moment within the timeline of the painting that I became aware of a predictability or automation that was forming, and were attempts to disrupt or redirect them. It’s kind of like you’re driving a boat in the harbour and you want go swimming near the shore, but you do not want to go to familiar places, so you just drive around in the open water until you see something interesting, and you head in and explore it. If it turns out to be a shitty place to swim, you turn around and go somewhere else. Then you swim until you’re cold and then you go home. So thinking about painting in relation to time spent wandering feels more fruitful than thinking about the construction of an image.

The idea that a painter’s job is to kind of ‘mechanically execute’ a pre-conceived image is responsible for a lot of bad painting — something every single artist is guilty of at some point or another. In my recent work there is no real construction of an image happening; but more a construction of a timeline. It seems that one of the key pillars of good painting is an artist’s confidence in their ability to ‘change their mind’ and to engage that skill thoughtfully and consistently in a given a timeline.

On the subject of timelines — you created each work strictly one work at a time, titled by the dates they were made, and presented in the show chronologically. How do you think this changes the way viewer experiences the exhibition?

Well, in hindsight the show is really about vulnerability. So I thought it would be best to stay faithful to this in how the show is presented by allowing an audience to follow the making of the show from start to finish. If one looks carefully, one can trace all the decision-making, insecurities, mistakes, and rationalisation in the making of the show. The chronicity of the show is crucial in giving the audience access — and it just kind of feels amazing to ‘come clean’ about your process and eliminate any sort of contrivance.

Alongside the paintings, your show includes four large hand-painted rugs, which feel both grounded and symbolic. What drew you to working with rugs as part of this exhibition, and what role do you see them playing within the overall show?

I was trying to introduce the idea of these paintings in dialogue with rugs — I actually am making a lot more and plan to develop them into more complex spatial arrangements, but one step at a time. You don’t become a rug-man overnight. Having said that, I am more interested in what happens when I make the rugs and the paintings at the same time — carefully monitoring each processes influence on the other. I think the significance of this is clear and also open to interpretation.

C L E A R I N G, Los Angeles, May 31, 2025 - July 26, 2025

Tell us a bit about how you spend your day / studio routine? What is your studio like?

I am a morning person. I get up these days around 6am, go straight to the studio, drink coffee and absorb the studio, draw, fuck around, and then at some point I just get fuelled and go for it, often not stopping for 8 hours. I then seem to just drop the tools abruptly, get out of there, and get on with my life.

What artwork have you seen recently that has resonated with you?

The last painting I remember blowing me away was Sir Thomas Lawrence’s portrait of Charles Lambton as a child, which is housed at the National Gallery in London. It is almost a pastiche of a perfect painting. I won’t describe it because I think it should be required viewing, but I would be shocked to hear of somebody truly disliking that picture.

Is there anything new and exciting in the pipeline you would like to tell us about?

I am making some sculpture and larger format rugs for upcoming shows. And some smaller paintings. I will always make paintings, but introducing other mediums in my practice helps challenge the intention behind the medium of painting, and makes the paintings stronger.

All images courtesy of the artist

Interview publish date: 23/07/2025

Interview by Richard Starbuck