Noga Shatz

“Unstretching the canvas and letting it hang freely breaks away from the traditional, rigid frame associated with painting and the authoritative male gaze... This fluidity speaks to queerness, to identities and bodies that resist containment or categorization.”

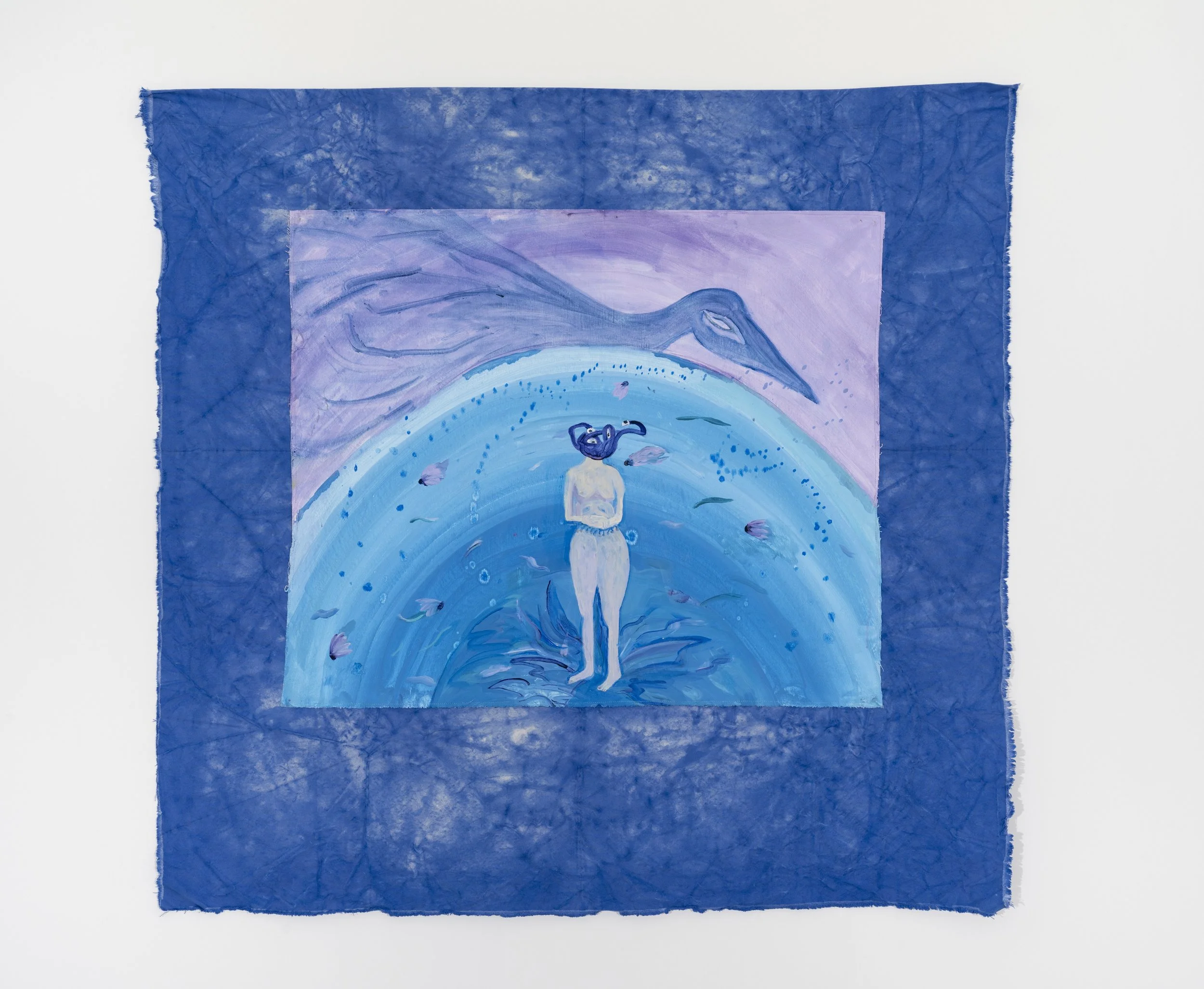

Noga Shatz is a multidisciplinary artist working across painting, printmaking, and music. Her work explores layered queer identities through historical and mythological narratives, often reimagining figures like Venus and Medusa to challenge dominant ideas about power, autonomy, and the feminine. Blurring the lines between image, object, and ritual, Shatz uses hand-dyed fabrics, translucent layering, and deep blues to create spaces that are both intimate and defiant. In this interview, she reflects on reclaiming domestic space, the emotional resonance of colour, and upcoming projects that push her practice into new performative territory.

Could you tell us a bit about yourself and your background?

I'm a multidisciplinary artist working across painting, printmaking, and music. My work explores layered queer identities through historical, mythological, and feminine narratives—often focusing on the demonization of queer widows and single women during 16th and 17th-century witch trials, as well as mythic figures like Venus and Medusa. These stories help me examine how power, autonomy, and otherness have been negotiated through time.

I hold an MFA from the Slade School of Fine Art and recently completed a PGCHE at Falmouth University. Recent exhibitions include Theia at Niru Ratnam Gallery (2024) and 50,000 Witches at One Paved Court (2023). Alongside my art-practice, I'm also the founder of The Open Art Club—an LGBTQ+ led social arts initiative in East London. My practice is both personal and socially engaged, weaving together material experimentation, historical research, and community to question dominant narratives and explore identity, resilience, and self-expression.

Your paintings often blur the line between image and object by using hand-dyed, unstretched fabric that hangs like a soft sculpture. How does this shift in material and form reflect your exploration of queer identity and the domestic space?

This shift in material and form is deeply connected to my ongoing exploration of layered queer identities, and to reclaiming the domestic space as a site of agency and transformation. I began dyeing my canvases by hand in my own bathtub—a quiet, intimate gesture that contrasts with the often grand, masculine-coded narratives of painting. These acts, rooted in care and ritual, allow me to embed personal and bodily presence into the work from the very beginning.

Unstretching the canvas and letting it hang freely breaks away from the traditional, rigid frame associated with painting and the authoritative male gaze. Instead, the cloth becomes sculptural—soft, fluid, and mobile. This fluidity speaks to queerness, to identities and bodies that resist containment or categorization. It also connects to the historical and cultural legacy of textiles, long aligned with “women’s work,” domestic labor, and undervalued forms of creation.

By embracing these materials and processes, I’m intentionally shifting painting into a space that is more vulnerable, tactile, and open to transformation—qualities I associate with both queerness and resilience. The work becomes not just an image, but a presence—something that hangs, floats, drapes, and holds memory.

Theia Exhibition view at Niru Ratnam Gallery, 2024

Self Portrait as A Witch

Inland Empire, 2024

How do mythological and historical narratives, such as Medusa or the witch trials, inform the way you depict bodies, power, and transformation in your work?

Mythological and historical narratives are central to how I approach the body in my work—it is a site of projection, fear, and resilience. The witch trials, particularly in 16th- and 17th-century Europe, weren’t merely superstitious episodes—they were state-sanctioned, religiously driven acts of control. In England, King James I’s Daemonologie reveals how deeply entrenched the fear of female autonomy was, even at the highest levels of power. Women who lived outside social norms—especially queer, widowed, single, or healing figures—were systematically demonized.

This societal fear echoes through Greek mythology, where female figures are either idealized or monstrous. Medusa and Venus sit at opposite ends of a narrow spectrum: the terrifying woman and the unattainable ideal—both stripped of agency and shaped by male desire.

In my Shiny Buried Things series (gouache on paper), shown at OPC Gallery and Niru Ratnam Gallery, I explored the ghostlike, buried body. Transparent layers reveal spectral figures, like traces of the historically silenced. In some of the works, I portrayed myself as a witch—trying on the title with curiosity and defiance. In another work, I reimagine The Birth of Venus as a figure fleeing the sea, clutching a severed head—reclaiming the myth’s violence and reframing feminine origin as active, not passive.

Your use of deep blues and layered figures creates an emotional atmosphere that feels both dreamlike and confrontational. What role does colour play in shaping the psychological tone of your paintings?

Colour is a deeply intuitive and emotional tool in my practice. I’m drawn to a range of blues because they hold a spiritual charge—both immersive and infinite. Historically, blue has been linked to depth, mystery, and introspection; for Kandinsky, it symbolised spirituality and longing for the eternal. These blues in my work create an inner landscape: like being underwater or inside a womb—spaces that offer safety, fluidity, a platform for change and transformation.

Within these spaces, my figures, often androgynous or ghostlike, can exist beyond myth or narrative, beyond binaries or fixed meaning. In this space they can just be.

The emotional weight of colour allows me to bypass language and speak directly to the body and senses. It creates a tone that is contemplative, sometimes confrontational, yet always intimate.

The Birth of Venus, 2024

We Need To Talk, 2024

We Need To Talk, 2024

Tell us a bit about how you spend your day / studio routine? What is your studio like?

My studio is in Walthamstow, at Blackhorse Lane Studios—part of Barbican Arts Group Trust. It’s filled with natural light from tall vertical windows that let in the sky, the rain, and the occasional pigeon tapping on the glass. The space holds both finished works and pieces in progress. I often take photographs, print them out, and use them as references or starting points when painting.

Most days,I work with music, usually playlists I’ve made or particular artists that match the mood I’m in. Lately, I’ve also found a lot of focus working in silence.

The studio often feels like an extension of me—chaotic, contemplative, always shifting. Even when I’m not there, I find myself mentally returning to it, visualising work, sketching ideas in my head, or drawing them down in my sketchbook.

What artwork have you seen recently that has resonated with you?

Looking back, I’ve seen quite a few powerful works over the past year that really stayed with me. I’ll name three.

Eunjo Lee’s solo exhibition When Forgiving the Sunlight at Niru Ratnam Gallery (February 2025) was incredibly moving. Her digital film was mesmerizing—a sensory, bodily experience that lingered long after viewing.

Marlene Dumas’ show at Frith Street Gallery (November 2024) also had a big impact on me. I’ve long admired her ability to merge image and material so completely. Her paintings feel inseparable from the emotions they evoke—tangled, raw, and haunting. Though it wasn’t recent, I still think about it often.

And finally, Tarrah Krajnak, one of the shortlisted artists for the 2025 Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation Prize. Her work integrates photography, performance, and installation with ritualistic and experimental gestures. Her approach resonates deeply with my own—especially in how she navigates personal and political histories through the body.

Is there anything new and exciting in the pipeline you would like to tell us about?

Yes! My work has been selected for the 9th Drawing Biennale this November (2025), where I’ll be showing a series of monoprints on delicate tissue paper.

I’ve also been awarded a month-long residency at ZARATAN in Lisbon, December 2025. During that time, I’ll be developing new work that weaves together movement, storytelling, and performance—pushing my practice into more immersive, time-based forms. I’m especially interested in how fabric can act as a performative object, carrying memory, motion, and meaning. It’s a unique opportunity to deepen my research and experiment outside of my London context.

All images courtesy of the artist

Interview publish date: 23/07/2025

Interview by Richard Starbuck