Tom Worsfold

“The screen is a bodily appendage in more ways than one. This inspires the way I render the body. Glossy ideals betrayed by leaky imperfections and corporate control. Sometimes it is disturbing to remember I am flawed, fleshy, mortal matter.”

Interview by Jane Hayes Greenwood

Since graduating from the RA you have presented two fantastic solo shows. The first, Apparition was at Carlos / Ishikawa in 2017; and the second: Models was at Castor Projects in January 2019. In these exhibitions, there was tension between humour and unease in the paintings, with bodies appearing fragmented, dissected, distorted or connected to other bodies or machines. Can you talk about the way you use bodies in your work?

Ever since I began making self-portraits at the Slade, the figure has remained a central part of my work. I am drawn to the body because it represents a kind of interface between states. A painted body is a code. As you mention, in recent paintings, the human figure is less immediately visible, and instead appears fragmented, often synthesised with everyday forms, like leaves or pipework. On reflection, this happened in reaction to the way a ‘whole’ body has a particular readability, and association with narrative - which doesn’t interest me. ‘Dissecting’ enables a different focus. I see the paintings akin to still lives (e.g. de Chirico, Armstrong, Clough) where signs of the body are treated like abstract shapes.

I think some of the humour comes from the detached way I treat bodies: the figure is presented as a ‘collection’ of surfaces and bits. Quotidian objects stand in for the self. I have always loved paintings in which bodies have an artificial, distorted look - the ‘Mannerist’ painters come to mind. In interviews, Francis Bacon describes the tension, as he sees it, between the illustrative/diagrammatic, and the felt/sensory. I am drawn to painting that straddles this same line. To me, the ubiquitous body-as-sign is curious: emojis, cartoons, safety notices, advertising, politics etc. Beginning with symbols, I probe these linguistic figures for humour, abjection, and beauty.

The paintings in Apparition seemed to deal with the dark side of human drives. Charged with a psychosexual pulse, violence, death and fetishistic activities were all featured or implied. What is the relationship to horror and abjection in these works?

Looking back, these works definitely have a dark tone. I was thinking a lot about social realism - troubled, urban imagery, full of isolation and dissemblance. They are satirical in part: a West-London townhouse ransacked by burly builders; a brutal airport bag inspection; yuppies and gym bags on commuter trains. I saw the canvas as a site to layer projections of anxiety - where psychic undercurrents of urban life could be evoked. I started to experiment with the psychological impressions I could give to ‘real’ places, and embraced the pictorial logic of the comic - in technique/aesthetic, but also in the way narrative is compressed. I was working a lot with diluted paint to suggest stained, organic, and bloody.

The paintings have an uneasy feeling which comes from rendering the body on both a micro/macro level. Abjection remains a relevant idea in contemporary figurative painting. I increasingly relate to myself in a language of self-improvement. We are bombarded by promises of transformation … told to live our best lives. The self is a technology which is our responsibility to manage through the right products, lifestyles and applications. The screen is a bodily appendage in more ways than one. This inspires the way I render the body. Glossy ideals betrayed by leaky imperfections and corporate control. Sometimes it is disturbing to remember I am flawed, fleshy, mortal matter.

Installation view ‘Models’ at Castor, 2018 Photo by Corey Bartle Sanderson

In a painting like “Waiting” we see a body unwrapped. Without flesh, this frail deathly creature stands at a window, gazing out of a Venetian blind, penis erect. Behind them, we see a murderous scene: blood stained knives and what looks like a giant soiled sanitary towel. There is an atmosphere of intense paranoia and it is ambiguous whether the vulnerable body we see is victim or perpetrator. Can you elaborate on this encoded work and your use of symbolism in the paintings more generally?

I never plan the works. I make the paintings a bit like the the surrealist ‘exquisite corpse’ method, adding bits as I go, responding to the previous day’s work. So the symbolism develops over time, and often ends up confounding me. I don’t see the paintings in terms of narrative; more in terms of sensation or state. It always sounds strange to me when I describe the paintings in detail, but I’ll say this one started with a simple colour contrast: brown and scarlet (I had just seen Sickert’s stunning “Minnie Cunningham at the Old Bedford” at Tate Britain). The brown blotches of fluid paint on canvas became a smoke-stained London flat, with a sink full of dirty plates and steak knives. The paintings often have a strong sense of voyeurism, and this is no exception. The figure itself has been completely undressed down to its nervous system. I was thinking how to depict a stagnant state … waiting for something … festering indecision … watching the world go by.

Despite the desperate scene in “Waiting”, as with all your paintings, the surface of the canvas is utterly seductive. Acrylic paint appears like watercolour at times and every square centimetre is treated with absolute sensitivity. Could you tell us more about the way you use paint?

To me, it is important these paintings are seen in the flesh. I like the idea that they operate in different ways, in different contexts: on the screen they appear graphic and flat; up close, the surfaces are textured, layered and optical. I want the surfaces to be delicious things … overindulgent somehow. I work mainly with acrylic paint because of its speed, control and artificiality. I see the inventory of paint techniques as a code, which can be modulated according to the subject. I have a geekish fascination with paint, and am often researching new mediums, effects and applications. I love learning about what paint can do, and how it can relate to other ‘looks’. The paintings imagine what’s underneath things, the essence of things. How can paint lend itself to this enquiry? Containing different speeds, attention-spans, styles, I am interested in the synthetic experience native to painting.

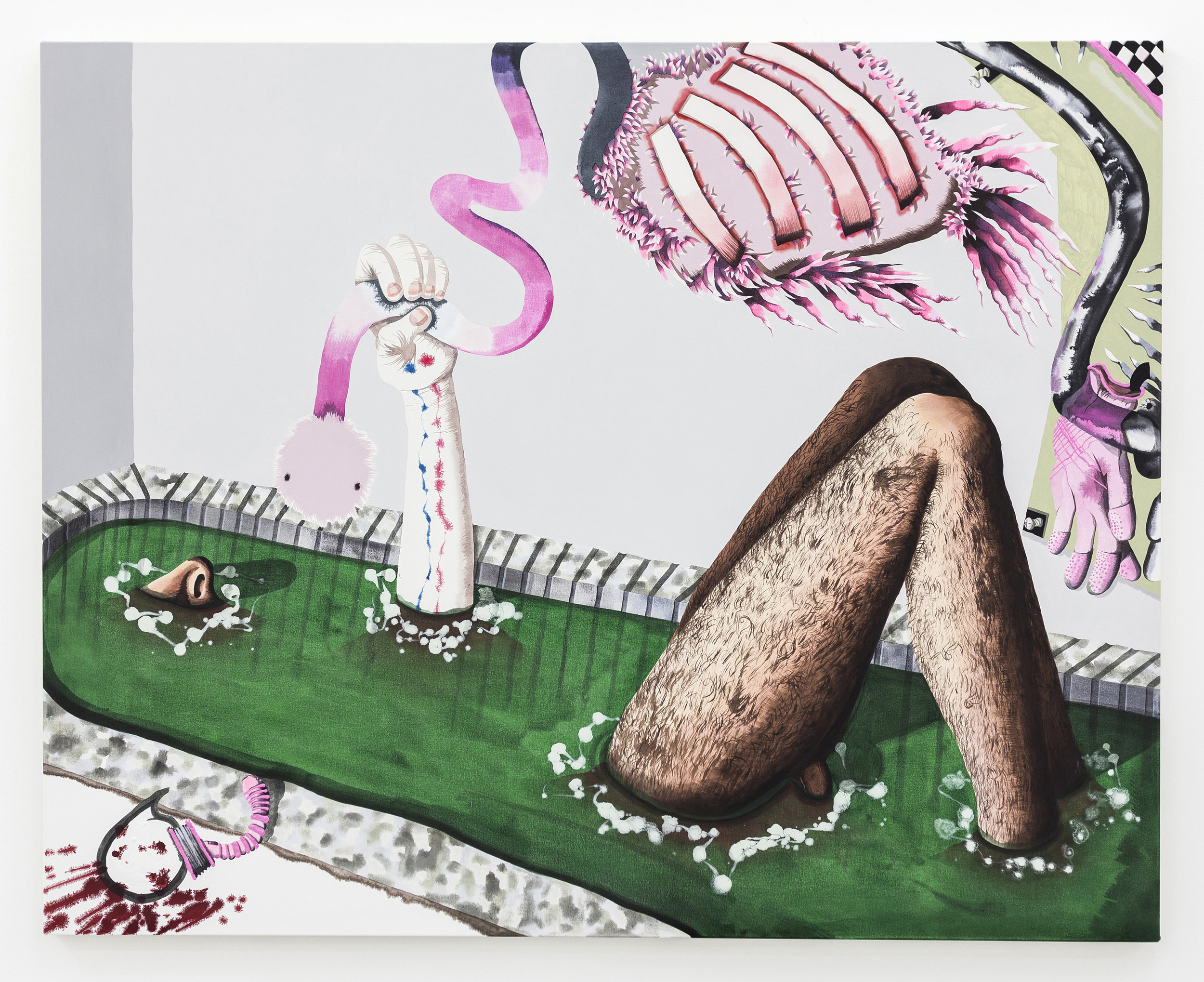

Shopping, 2018 Photo by Corey Bartle Sanderson

Waiting, 2017

Balloons, 2019

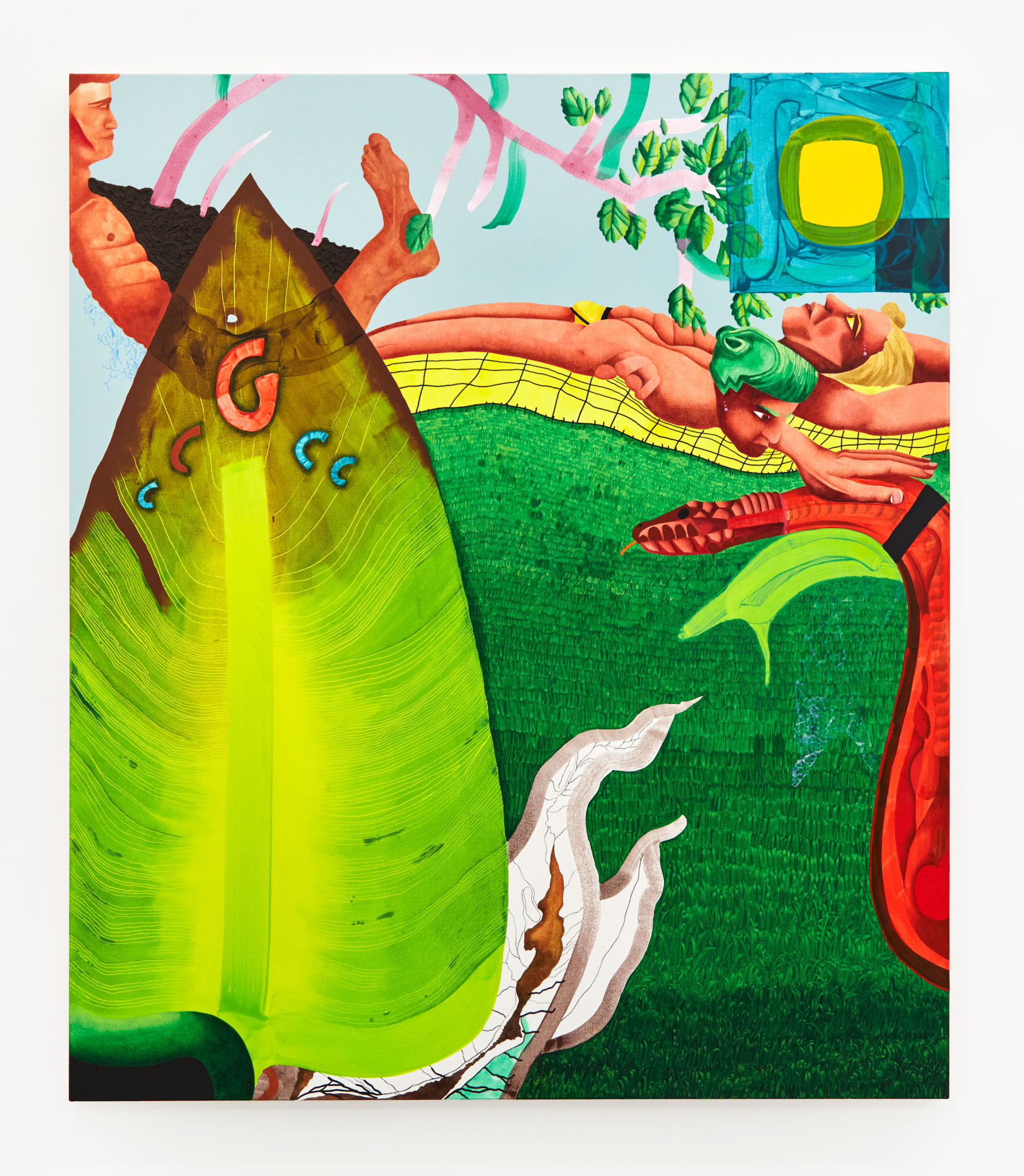

Garden, 2018 Photo by Corey Bartle Sanderson

The paintings in “Models” felt slightly lighter than those in “Apparition” but no less complex. The titles seemed to refer to banal things or everyday experiences like “Shopping” and “Garden”. Could you expand on your use of titles and the disjuncture between these references to the ordinary and the enigmatic depictions?

The titles in this show were meant to sound very banal and deadpan. I like titles that provide minimal information, without framing the paintings too much. It is important that these works have their roots in the world, but that they could still be excuses for fantasy. I was imagining a children's picture-book of primary shapes: leaf, tongue, garden, hand, bottle etc. Compositionally, I used these big shapes as starting points - projecting fantastical ideas and thought processes onto them. For me, by using this fairly open system of signs like a code, I saw each one as a sort of model for personal feelings and internal states.

I know you make lots of drawings. Is this something that prefigures the paintings when you are building a composition or is this a separate part of your practice?

To me, they are completely separate processes, which inform each other nonetheless. I work in phases of painting and drawing - one always satisfying something missing in the other. I never tend to plan the paintings in advance, and work directly onto canvas. This means they take longer to complete, with lots of intensive staring time in between painting. Drawing is much quicker - forms reveal themselves with a definiteness - they ask something different. The drawings allow me to be much more illustrative in the way I imagine the figure in the world. A recent series of drawings called ‘Felt tip’ were all self-portraits, where my body merged with everyday objects, like hand-sanitiser, or a football.

Apparition, 2017

Football, 2018

Tongue, 2018 Photo by Corey Bartle Sanderson

Who would cite as artistic influences?

Lari Pittman is an artist I look up to - I admire the way he develops these immaculate, difficult frameworks for a highly coded, personal iconography. Bacon and Hockney are two other major influences. Some other names: George Tooker, Paul Cadmus, and Martin Wong for their beautiful depictions of American life. Prunella Clough for the way she abstracts forms from the world. Jill Mulleady, Liz Arnold, and Dorothea Tanning for their affecting, magic-realist character studies. More recently, I have been enjoying Michael Stamm’s work - his paintings are like gems.

Could you tell us a little about your background and where you studied?

I completed my undergraduate at the Slade School of Fine Art, and then went on to study at the Royal Academy Schools. My work owes a lot to these courses, as well as the great friends I made there. Since graduating, I have continued painting as much as possible.

Could you tell us what you're working on next?

Back to the studio after a short period away. More self-portraits. I am trying out some new materials and methods. Watch this space!

All images are courtesy of the artist

Publish date: 21/08/19