Hedley Roberts

“My work is all about what is not known, evident or visible. I’m really interested in how we ‘know’ each other, how we assess our knowledge of each other, and how we continually renegotiate our relationship to each other.”

Interview by: Stephen Feather

Could you tell us a bit about yourself and your background? Where did you study?

You could say that adolescent desire led to me discover art. I grew up in a remote part of East Cornwall, not near the sea. In 1982, my mother bought a book from a book club. “A Picture History of Art” by Christopher Lloyd. Until then, I didn’t know what ‘art’ was, what ‘artists’ did, or that I could be one. The book showed pictures of naked people. I remember at the time thinking an artist must be like the pop stars that I saw on the TV. When I was 15 years old, an older girl who lived nearby needed a friend to go with her to a Saturday art class at Plymouth Art School, over 20 miles and 2 hours away. When I got there I decided that this was where I wanted to be. From there I went to Falmouth College of Art, Central Saint Martins. I completed my MA at the Royal College of Art at 23 years old. I also did a period at the School of Visual Arts New York. 20 years later I did a Doctorate in Fine Art at the University of East London.

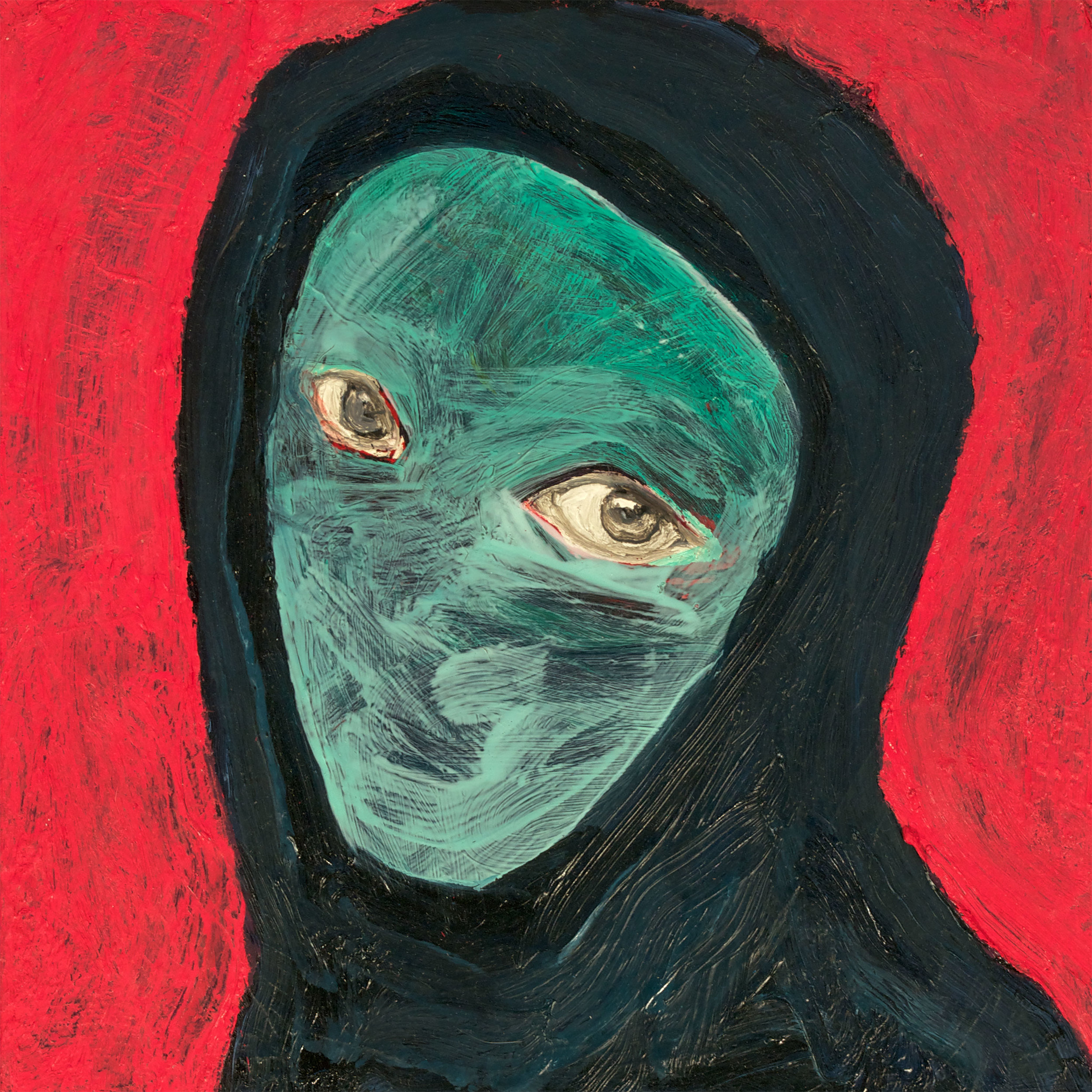

In your work you specialise in making pictures of people from images on social media. These ‘non-portraits’ are painted over in stages and finally sit in between representation and abstraction. Is what is not seen in these portraits as important as what is visible?

My work is all about what is not known, evident or visible. I’m really interested in how we ‘know’ each other, how we assess our knowledge of each other, and how we continually renegotiate our relationship to each other. In neuroscience there is a claim that there is specific part of the brain that specialised in facial recognition. Neuroscience also thinks that the brain ‘sees’ and interprets new information from the eyes quickly by piecing together using prior knowledge. So our brains are not reading every detail about the persons face, instead its making an approximation from an amalgam of data. Also, when we interact with each other we have ‘a priori’ sense that the other person has consciousness, and has a human experience that is basically similar to our own. In actuality we cannot have empirical knowledge of their experience of being – we cannot truly ‘know’ the other person, we can only guess. Our human experience and our ‘knowledge’ of each other is always guessing at what is not visible.

Art Student 2016

Londonfields

Dogtown Oracle 2019

Your practise involves studying a lot of faces. Are there certain facial forms or compositions that attract you in your work?

For a long time I’ve been interested in the ‘look’ that people use when they photograph themselves. When I ask people to send me images, I always ask them to send their best ‘selfie’. The way they perform their best version of themselves, how they understand the camera, the revisions they make to get the best image. All of this is contained in the image. In making my composition I’ll think about and test lots of formal structures, making minor edits on the composition throughout the painting. In the end I’ve removed or obliterated a lot of the data and replaced it with new information in the form of paint.

Your pictures undergo several stages of painting and transformations. How do you know when you have resolved a piece of work?

Haha. I’m never 100% sure. There’s always a suspicion that it could be resolved in another way in some parallel dimension. Sometimes I’ll get stuck with an unresolved painting and return to it years later and I’ll have what I need to make it work. I suppose, for me, making a painting is like having a relationship. It has a timeline of its own to be negotiated. In the end there does have to be a moment at which you decide that its over and you shouldn’t go back.

You’ve said that “The other in the painting is my internet friend, my acquaintance, colleague, family, stranger, lover.” Does your practice change your own perception of the sitter?

As I make the paintings, I realise I know very little about the sitter - even if I start with someone I know intimately. The painting progresses, and I obliterate the image with subsequent layers of painting. As I do this, assumptions and stereotypes begin to fill the gap between my poor knowledge of the person and my awareness of them as a separate entity, an ‘other’. The paint then begins to function as a visceral experience of the gap, gradually becoming a material veil, a metaphor for my failure to be able to know the sitter.

What artwork have you seen recently that has resonated with you?

That’s a hard question. Our lives are saturated with imagery. My Instagram feed passes tens of thousands of paintings across my day. But... the painting that I can never get out of my head is Augustus John’s 1919 portrait of the Marchesa Casati. A wealthy bohemian heiress that died penniless, She had over 100 portraits made of her. John was her lover and painted her 3 times. The 1919 portrait is stupendous. It’s the best known, and is considered the most captivating, but it’s also almost completely constructed from stylistic tropes - big red hair, kohl eyes, rouged lips and cheeks, alabaster skin, translucent blouse, fantasy landscape, brushy expressionistic paint handling. It’s a portrait, but it’s all outward facing ‘image’. Fascinating.

Professor

Gammon

Hoody 2017

Other Portraits, New Art Projects Gallery, London

Tell us a bit about how you spend your day / studio routine? What is your studio like?

The best days start with the sun waking me next to my partner, a walk with my dog and some good coffee in a familiar cafe. I’ll spend an hour doing email, social media and admin. Then I’ll go to the studio and spend some time tidying up, moving things around while I look at whatever is on the easel. The paintings can take months to dry so I’ll check them. I’ll begin with some small workings on paper and gradually work up to making some big changes to works that are in development. I’ve always got lots of different works at different stages. Some stay like that for years, before they get the ‘solution’. The last period of the day is usually something quite dramatic. The last thing I’ll do is photograph what I’ve done on my phone, so I can look at it over coffee the next day.

Is there anything new and exciting in the pipeline you would like to tell us about?

Well, I’m Head of Luton’s School of Art & Design at the University of Bedfordshire, which is a really big project doing good things with the Creative Quarter development, Luton Football Club and a future bid for City of Culture among other things. However, I love planning ahead, so I’ve also got a really big project that’s completely confidential so I can’t talk about it yet, but I’m really stoked about it. In terms of exhibiting, I’m continuing to work with Rasmus Fischer at Galerie Wolfsen in Aalborg alongside artists Corey Lamb, Henrik Godsk, Rune Christensen and Jordy Kerwick. I’m also in discussions about future projects with Cross Lane Projects in Kendal, Piermarq in Sydney, a gallery in Ireland, and another in Beijing.

All images courtesy of the artist

Publish date: 02/04/2019