Nayoung Kang

“Lighting plays a significant role in my art practice”

Interview by: Simek Shropshire

Could you tell us a bit about yourself and your background? Where did you study?

I am a London-based artist from South Korea. I moved to the UK in 2011 to begin my BA at the University of Leeds, afterwards, in 2016, I completed an MA at the Royal College of Art and have continued to live and work in London. Ever since my early childhood I have come into contact with art, watching my uncle who is a famous painter in Korea. I started studying art at Seoul Arts High School but I was not able to adjust to the Korean art education system, which required more skill and competitiveness than it did creativity. It was for this reason that I decided to come to the UK.

My decision to move to England has changed my life completely. I have spent most of my twenties living in England as a foreigner, therefore my personality, experiences and the struggles that I face are impacted by language and cultural difference, which have been embodied in my art practice. My life in England and my life in Korea are so different and even if the UK is more of a familiar and comfortable place to me now, I am still a wanderer who does not belong anywhere else; I think I am quite enjoying this status.

Moon Street 2018 (installation view) at Laser Gallery in Seoul, Korea

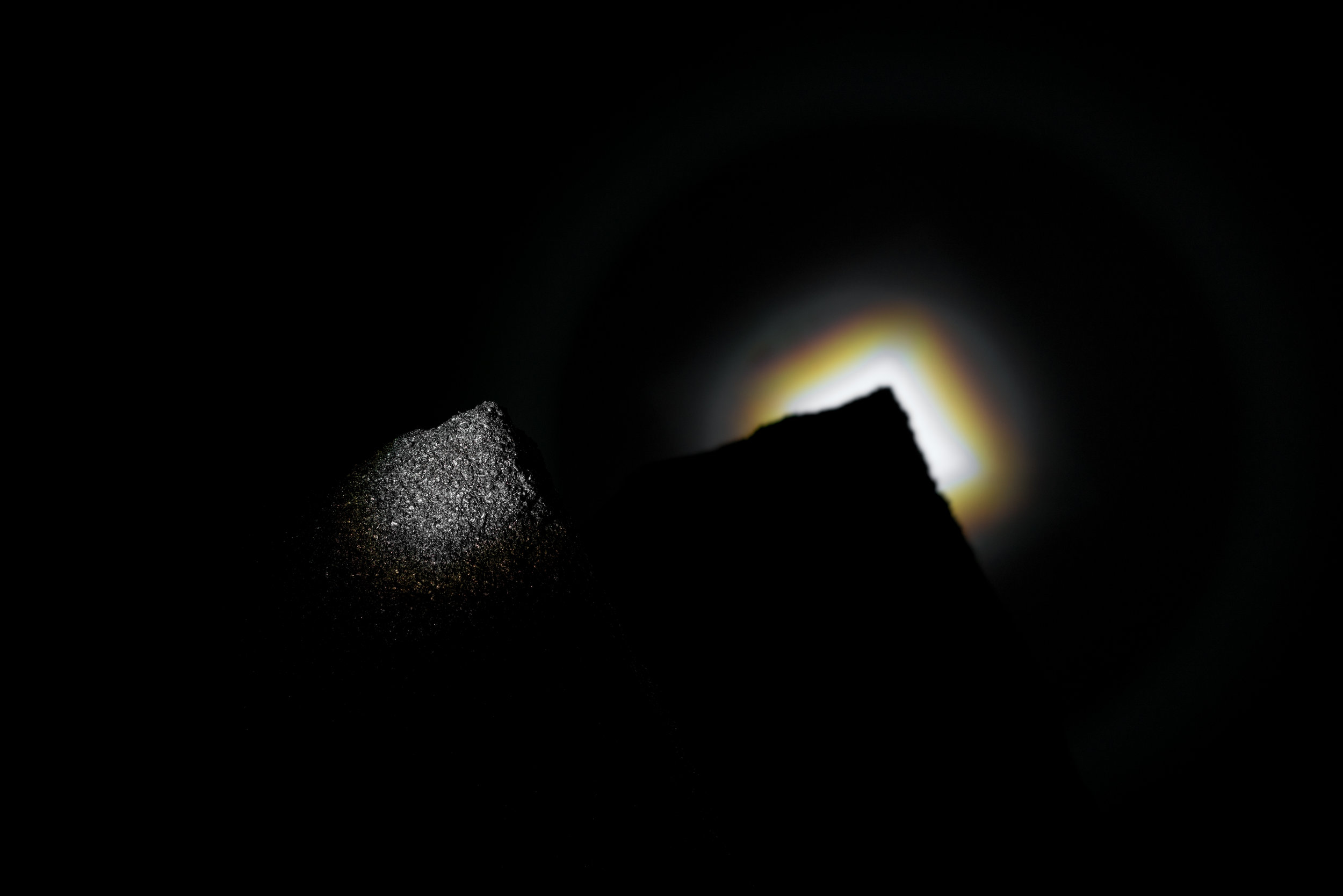

Moon Street 2018

Moon Street 2018 (details 1) at Laser Gallery in Seoul, Korea

Your work is rooted in your personal struggles with displacement, lending to installation pieces and photographs that present a psychological, visual, and physical darkness and emptiness that can, at times, be difficult for the viewer to encounter. To what extent does your practice aim to unsettle the audience and do you find that doing so is effective?

My art practice comes from my personal stories and suffering but I do not ask audiences to be aware of the particularities of this backstory or to read this information directly in my work. The thing that I am trying to avoid when showing my work, is forcing people to see the evocation of my sense of suffering. Even if ideas and motifs in my work are based on my emotional experience the intention behind my work is not that people directly come into contact with this, but rather, I would prefer to see unpredictable interactions with my artwork. Some people might see my work and feel the struggles that I have felt by connecting with their own experiences, or, others may sense the contrary and feel comforted by my work by allowing it to tap into good memories. It is always good to share and exchange feelings, however, I actually seek to make my work open so that it can be read differently and variously.

For instance, my projects, such as Moon Street (2018) or Glimpse of Other Story (2018), were inspired by my environment, where I was situated and everything that I was encountering at the time, but the work does not speak directly about the difficulties that I was experiencing. Combining sound, light, text and other media, the work is more focused on making a poetic or nostalgic atmosphere within a space for people to come into contact with. Of course, if you feel uncomfortable, or unsettled when you see my work, this is also a welcome and valid response. It is important to think about how much my personal life impacts on the working process and then how the work is transformed by being presented to the public.

How does light manipulation in your site-specific installation works, such as “Glimpse of Other Story,” provide a theatrical escape from darkness?

Lighting plays a significant role in my art practice and performs two different functions: firstly, as most of my works are displayed in dark spaces, it makes the artwork visible so that it can be viewed, the same way that one might switch on a lamp to read a book; secondly, the light itself has an important meaning and speaks of different stories apparent in my work, as I do not only choose a dark environment for my work because it speaks of the night (as my inspiration and visual motifs come from the world at night). Showing the work in a dark room makes a big difference to the whole atmosphere of the space; various elements such as the darkness, sound and installation objects are combined through various lights, which create a new space, allowing us to make our way in the dark.

The lighting in Glimpse of Other Story is a very important element. I installed an amber strobe light into large spinning curtains, so that the light comes out of the gaps in the fabric, illuminating the entire space as it rotates. The idea behind this installation is to reflect an old obsession of mine: every time a car passed by the window, its lights lit up the whole room in yellow, making it harder for me to sleep at night. The amber light transformed into a theatrical set in my work with rotating curtains and busking music, which makes the installation completely different from my memory. I remember that one member of the public told me that the installation reminded her of a merry-go-round in an amusement park at night.

Glimps of Other Story 2018 at Safehouse 2 Gallery in London

The subjects of your three “Dead Place Project” series are abandoned and dilapidated buildings, all of which were photographed in the middle of winter. Why do you refer to the ruinous buildings as “dead spaces”? Are the natural surroundings, shrouded in dead fauna and blanketed in snow, intended to exacerbate feelings of an all-encompassing ‘death’?

It was an extremely cold winter at the time when I encountered abandoned buildings located in a rural area where my previous studio was. It was a place that was particularly dilapidated, all the farms and houses were not cared for at all. I discovered so many deserted places, which was how I started the Dead Place Project. This place was silent, abandoned and had fallen into disrepair, it was dark and devoid of life—both humans and plants alike.

I began capturing its 'dead breath' with my camera—the faded furniture, rusty pipes and decaying marks became the subject and material of my art. I believe that all of the natural surroundings with the buildings came to me together at once by chance, which caught my attention and it seemed like the landscape was crying for help. The natural environment, time and that space were all seemingly dying, but also paradoxically, the place existed as a living ‘death’. I think that I was invited into this place in order to deliver it to the world as it is, rather than expressing and representing it intentionally. I call it ‘dead place’ because it does not mean just physically lifeless or a deceased place, it also creates another existence, one which is powerful and beautiful, resonating with its own unique spirit.

144, Jisam-ro, Dead Place Project #2, 2013

242, Seongbok 2-ro, Dead Place Project 2013

Leftovers by 564-1, Jigok-dong 2014

Leftovers by 144, Jisam-ro #1 2014

Tell us a bit about how you spend your day / studio routine? What is your studio like?

I have a studio that I share with my friend at the moment in Bromley-by-Bow, East London. I am working in a cafe part time and trying to go to the studio for the rest of the day. When I stay in my studio, I usually start by doing some drawing, reading, writing and researching with some coffee, which turns into an idea for testing an installation. And then I browse materials and order them online. I am trying to do lots of drawing because sometimes they become artworks themselves or sometimes important plans for making physical installations. I like attaching my drawings, texts, notes, digital images and any inspiring things on the walls of studio. My studio is full of industrial materials such as cement, plaster, metal, lights and tarmac, etc., I usually spend time playing around with them.

What artwork have you seen recently that has resonated with you?

A recent show, Lawrence Abu Hamdan’s Earwitness Theatre at Chisenhale Gallery was very impressive. Abu Hamdan’s political content within the sound work, text and objects worked together very well in the exhibition, which inspired me in the way that sound can be used to be so powerful. I think Abu Hamdan very effectively re-constructed his political investigation by transforming it into an acoustic installation. I found one of his audio works especially immersive. It was situated in a dark listening room where you could hear human voices (earwitness), the sonic memory of the military prison Saydnaya in Syria. I have come to think that with just one sound an intense message can be delivered in a manner better than anything else.

Is there anything new and exciting in the pipeline you would like to tell us about?

Currently I am working on a project involving urban foxes and the sonic environment, which I have been planning for a long time. In my previous work, I exhibited a real foxtail with a small whistling sound and cooing noise made by me. Developing this work, I am experimenting with some city soundscape that I have collected and am trying to invite real foxes into my work, which will be another opportunity to perceive and respond to my current context. This work will be presented at an upcoming show in March 2019 at Subsidiary Projects, a domestic exhibition space in London, organised by Dateagle Art.

All images are courtesy of the artist

Date of publication: 21/01/19