Zavier Ellis

“I mostly break up language and visual elements as I prefer incoherence and ambiguity, so that the audience might decode elements, but also take it to wherever they want to go.”

Interview by: Brooke Hailey Hoffert

Could you tell us a bit about yourself and your background. Where did you study?

I’ve always approached art from all angles. After being switched on at a very young age and being absorbed throughout my school years, I decided to study Art History. I went to Manchester University and read History of Modern Art, but also had a studio in my attic and kept up with photography. I began running club nights where we would combine DJ’s, live music, slide shows, live graffiti, etc. In fact, one of my co-conspirators was Alexis Milne of The Cult Of Rammellzee. We are still good friends and he and the Cult are an incredible, wild performance crew in London.

Towards the end of Manchester, it was either going into writing by way of art history or criticism, or the gallery business. When I left, I took an internship at a gallery in London and then went into partnership, and eventually opened my own gallery. Simultaneously, I always had a studio and whilst at the first gallery I undertook a Masters in Fine Art at City & Guilds of London Art School. This didn’t only make me a better artist, but also a better gallerist and curator.

So you can see, I’m into the circuitous, interconnectedness of things, and I’m not into prescribed notions of what we can, can’t, should and shouldn’t do.

'Gott mit uns', 2017

'This Deathly Love', 2017

You are featured in a group exhibition called The Discontents that opens in October at the Bermondsey Project Space. What can we expect from that exhibition?

It’s a simple but intriguing premise – the show will explore the studio practice of five artworld protagonists who are mostly known for their other work in the industry, including art criticism, journalism, running galleries, and curating. The other four are Matthew Collings, Tommaso Corvi-Mora, Matthew Higgs and Max Presneill. The title is a conceit that – to my mind at least - suggests we are not content to be doing just one thing. We need more than that and are polymathic in our approach. Kicking off Frieze week on October 2nd, it will be an event worth checking out.

What is it like to be an artist while juggling so many other roles in the art world?

Fundamentally it takes organisation. I have a pretty well-developed capability to switch my thinking, so depending on my schedule I can turn from this to that. Underneath it all though, is an awareness that everything is connected. I don’t think organising exhibitions and being in them; or curating work and making it; or writing and reading about it, are very far apart from each other. They are all necessary and any component can feed into the other. I only have one rule, and that’s to put the artists I work with first, but other than that they’re all for the breaking.

'Gold Standard: Freedom', 2017 (collaboration with Hendrik Zimmer)

'Black Standard: Freedom', 2016

'La République ou la Mort', 2018

What made you want to create a series that revolves around the French Revolution?

I think of the work as History Paintings. And the subject might be something that is a long-term interest, or that has recently come into view, or a combination. This series came from two directions. A German collector of mine once told me about the history of the German flag which caught my imagination, and as I researched it further it became more and more fascinating. Around it was revolution, and the birth of a great modern nation rooted in deep history, but also the opportunity to undo misinformation and conditioning, which underpins some of the work. It had already occurred to me that my work was resembling flags, and this led to a series based on revolutionary flags – first German, then Islamic black standards, and then French. Additionally, I had already made a small painting on the subject when I first began to read about it in 2011 so my ideas coalesced, and now is the right time to go in deep on a hugely fascinating, integral phase in European history.

How do you go about naming your work?

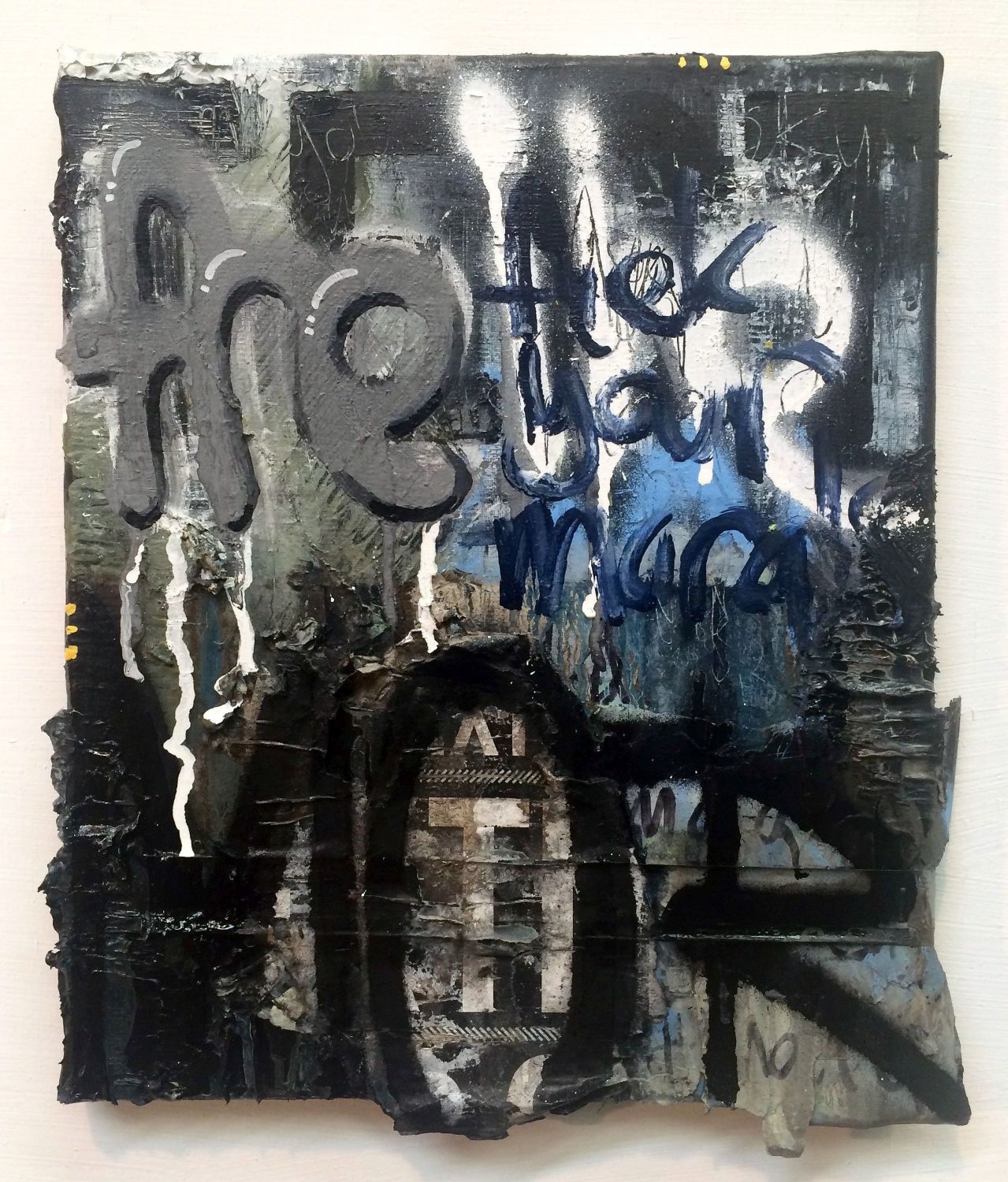

The titles are never incidental. Individual or groups of works are always heavily laden with content. They represent an investigation into a particular subject that really resonates with me at the time, which might be fleeting or ongoing. The research that goes into this has become more and more important and involved, and feeds directly into the work, so a series about religion or revolutionary flags or the occult will require a phenomenal amount of research. This directly informs the paintings, including choice of words and text, typeface, colour codes, measurements, collage elements etc. The paintings, particularly at large scale (currently up to 2x3m), will therefore become a labyrinthine receptor surface with their own internal, symbolic logic. I mostly break up language and visual elements as I prefer incoherence and ambiguity, so that the audience might decode elements, but also take it to wherever they want to go. The titles will always refer to the work’s subject, or topic, and so help the audience in a little further. But again, they are often oblique.

'Doctrine I', 2014 (cropped, click on image to enlarge)

'The Covenant', 2013

'Black Standard: Fuck Your Morals 1', 2016 (cropped, click on image to enlarge)

Tell us a bit about how you spend your day / studio routine? What is your studio like?

I rent a barn near where I live in Windsor, which is next to the M4 so its part rural, part industrial. I only work when I have a deadline as I’m so busy with other projects, and it’s rare to take a full day, so mostly I will take care of other work in the morning and then do an afternoon session. It’s a raw environment with untold industrial and fine art materials. If I’m working on a big piece then this is the main focus, and smaller works will spin off it. The process is quite brutal and mostly begins with a few set parameters, and swings from instinctive and action based, to slower, more refined work as the piece progresses. A big painting will take many, many months. Small paintings mostly take time too, but rarely, serendipitously, they just happen.

What artwork have you seen recently that has resonated with you?

The last blockbuster I ate up was Rauschenberg, who has been an influence since my Art History days. I was in Toulouse in the summer and was lucky enough to have a chance encounter with the incredible frescoes in the Salle des Illustres in the Capitole. These were on point in terms of my current research; technically superb; and a fascinating combination of political and mythological. In fact, my photographs of them became collage elements in the main 2x3m piece made for The Discontents. The summer is also about London art school degree shows, when I visit all the BA & MA exhibitions, and it’s a very strong year. There are some really exciting new, young artists about to hit us.

Apart from your group show titled ‘The Discontents’ Is there anything new and exciting in the pipeline you would like to tell us about?

I’m discussing a few art fair and exhibition opportunities for 2019 and working behind the scenes on a potentially huge project – all to be revealed if it happens - but right now it’s all eyes on The Discontents.

The show ‘The Discontents’ opens 2nd – 13th October 2018 at The Bermondsey Project Space, London.

Publish date: 02/10/2018

All Images are courtesy of the artist