Dawn Roe

"I always feel a need to be very cognisant and respectful of how and to what extent I draw upon specific narratives belonging to regions and communities where I am an outsider, particularly one based in the U.S. during yet another heartbreaking period in global politics."

Interview by writer Brooke Hailey Hoffert

Could you tell us a bit about yourself and your background. Where did you study?

In the early 1990s, I moved from Michigan to Portland, Oregon in the U.S. where I connected with various overlapping groups of visual artists, musicians, writers, poets, and zine-makers. The DIY culture prominent in Portland at the time informed much of my philosophy around art as culture, rather than commodity. My earliest education took place in bookstores like Powell’s City of Books and Reading Frenzy, where you could browse art books for hours and buy the latest zines or used books cheaply. But, I did eventually end up going back to college for a more formal education, and this began when I was introduced to The Northwest Film Center by filmmaker friends.

At the time, the film center had a relationship with Marylhurst College that allowed for cooperative coursework. So, I was able to pursue a B.F.A. in Photography from Marylhurst while continuing to take film classes toward my major coursework. This was a fortunate mix of circumstances, as these experiences really shaped my understanding of documentary and experimental styles of cinema and photography. During the final year of my undergraduate program, I was made aware of the Rural Documentary Collection at Illinois State University. This led me to pursue my M.F.A. degree at Illinois State, which was also a fortuitous turn of events as the cohort was very small, and interdisciplinary, which pushed me in directions that may not have occurred to me in a more discipline specific program. It was during my time in graduate school that I initially began to think very deliberately about how the still and moving image might come together in my work.

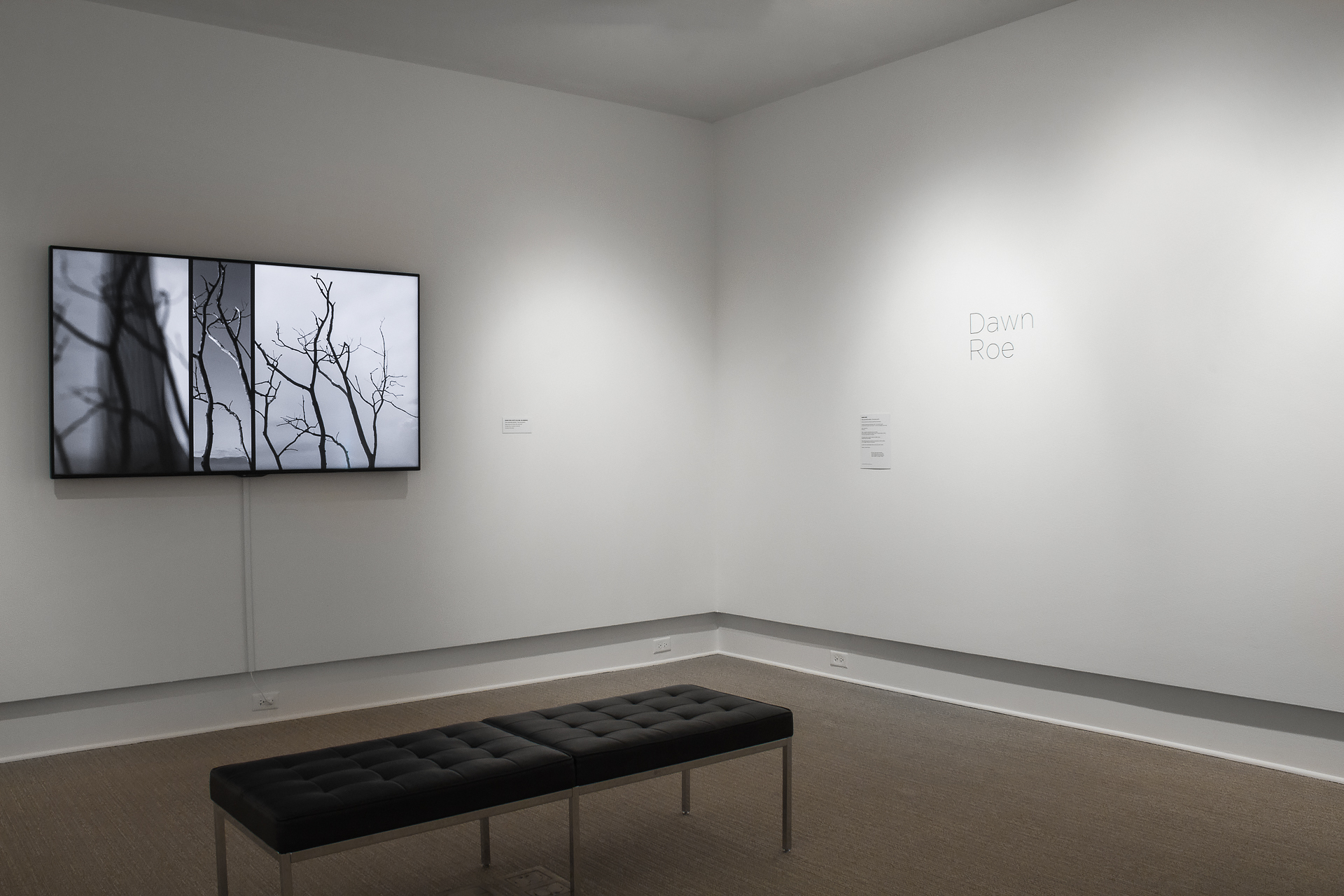

'Mountainfield Studies' The Florida Prize in Contemporary Art, 2016, Orlando Museum of Art. Photo credit: Tiffany Raulerson

'Mountainfield Studies'

Your work engages with the earth and certain landscapes. Where does your connection to landscape stem from and does the connection effect what type of art is created?

My initial engagement with landscape did not come from any particular attachment to nature, but more as a recognition of the landscape as a uniquely perceptual space – a situation, really. So yes, connecting in this way to landscape as a set of conditions that acknowledges its aesthetic embodiment as influenced as much by the cultural histories embedded within as its geological formation has definitely effected how I approach my work. Last summer I began a project in a very specific region, where this mode of thinking served as a vital foundation. Working in the Pyrenees Mountains along the Mediterranean coastline of Spain and France, I was engaging with the trails used as paths of exile during the Spanish Civil War and WWII, as well as the border town of Portbou – noted as the location of Walter Benjamin’s suicide following an ill-fated attempt to flee Nazi persecution in 1940.

That aspect is culturally significant, hugely so, but equally important is the memory of the hundreds of thousands of nameless people that crossed the same border as refugees. This innumerable body occupied my mind as I worked within these sites just as much as the singularity of Benjamin – it was an uneasy space.

There’s a lot jammed up into this, of course – a century+ of photographic history; romanticized aesthetics of landscape as well as contemporary responses to just that; mythologies around (mostly, always) men and their supposed rugged individualism as associated with their forays and adventures into various territories and topographies; etc. Most importantly though, I always feel a need to be very cognizant and respectful of how and to what extent to I draw upon specific narratives belonging to regions and communities where I am an outsider, particularly one based in the U.S. during yet another heartbreaking period in global politics.

The Sunshine Bores | The Daylights, 2016 Faculty Biennial, The Cornell Fine Arts Museum at Rollins College, Winter Park, FL

The Sunshine Bores | The Daylights

You have an interest in both still photography and digital video. How do you think both digital video and still photographs engage with the subject of your work differently?

This is something that I’m constantly grappling with. I have an ongoing conversation with myself about whether there is any sort of fundamental difference between documenting and recording – for whatever reason I tend to think of the still images that I capture in any given situation as documentation, and the video clips obtained as recordings. This has to do with time, for sure, but also cultural conventions, I think. The documentary image is so fundamental to photography, and it’s associated with iconic images that we presume show us a certain “truth” even though we are fully aware that every photograph is a contrivance. We still believe in the documentary image.

I tend to equate documenting with stop/start or beginning/middle/end as separate from one another or discrete parcels of time – which I guess I equate with the photograph. Whereas when I conjure the idea of recording I think of an endless flow, pushing “record” and letting time roll, and re-producing an illusion of real time through montage. I rely on the ontological differences between these materials to direct my approach to how I use them. I’m constantly questioning what a photograph is in-and-of-itself and how that mode of representation translates to film/video which is really just a rapid succession of individual frames, or lines of light. I try to think really carefully about the conventions of looking/seeing that have resulted from these representational strategies – and the expectations that accompany them – when I’m making work that engages with and depicts sites that are culturally, personally, and historically charged.

'Mountainfield Studies' The Florida Prize in Contemporary Art, 2016, Orlando Museum of Art.

How do you go about naming your work?

It depends on the project. Sometimes I’m thinking of things broadly, and other times there is much more specificity. For instance, after working in the Goldfields region of Australia some years back, I was immediately drawn to the succinct, descriptive quality of the place name as functioning perfectly for that work. This led me to fixate on the “field” within the term as a potential link back to the notion of the field study, so I continued to use that form in a couple of subsequent projects that were conceptually related – Airfield Studies, and Mountainfield Studies. Other titles come from literary or musical references, or from phrases or utterances I come across while researching. I don’t really give singular titles to individual works but tend to name projects as a whole.

The title for the most recent project, Conditions for an Unfinished Work of Mourning: Beauty as An Appeal to Join the Majority of Those Who Are Dead, came about as a result of engaging with a few Ariella Azoulay essays and one of her books, Death's Showcase: The Power of The Image in Contemporary Democracy. I came to this book as Azoulay takes up Benjamin's Work of Art essay throughout. In further researching contemporary responses to Benjamin’s notions of “aura,” I located a Miriam Hansen's essay, "Benjamin's Aura” which includes a reference to a particularly compelling footnote from “On Some Motifs on Baudelaire.” The project’s title and subtitle combine a passage in the Azoulay text with a paraphrase from the Benjamin footnote. This is an example of an extremely specific set of references!

Conditions for an Unfinished Work of Mourning: Beauty as An Appeal to Join the Majority of Those Who Are Dead. 2017-Ongoing

Tell us a bit about how you spend your day / studio routine? What is your studio like?

Much of my work has become computer-based over the years, which I’m used to now, but is pretty distinct from my early days of literally cutting and taping tiny celluloid strips of Super 8mm film, or working in a darkroom with negatives. I stopped working with analog materials around 2009 once I realized I could essentially achieve the same image quality as my medium format cameras with the newer DSLRs, and that these cameras would allow me to more seamlessly integrate still image with video, as the image quality would be more precisely the same.

These days my studio routine ebbs and flows in terms of what stage I’m in with any given project. Because I tend to seek out sites that are geographically distant from my home studio, I often apply to residencies that allow me to live and work within a particular space for periods of time. Generally, I collect large amounts of photographic and video-based footage and work within the studio space of the residency programs to begin producing initial studies. Then I subsequently work with all of the material at my home studio for many months at a time afterward. The space itself contains a high quality monitor for analyzing, editing and forming photo/video-based material, several hard drives for storage and transferring of files, a printer for making work proofs, a very long white wall for editing and sequencing images, various projectors and surfaces for testing out installation options, bits and pieces of material collected over the years for use in fabricated studio-based constructions to be photographed/videotaped, piles and stacks of books and paper always in various states of order and disarray, and of course, closets full of artwork.

What artwork have you seen recently that has resonated with you?

I have to say I was really pleased to have waited in line for two hours to see Tania Bruguera’s, Untitled (Havana, 2000), that was recently restaged at MoMA in New York. It was such a compelling perceptual/bodily experience that was (for me) the polar opposite of any sort of sensationalized spectacle – though it certainly draws on/relies upon a certain intensity. The use of the archival footage of Castro slowly revealing itself (and helping your eyes adjust to the otherwise completely blackened space) as emanating from a small monitor in the ceiling of the tunnel was a really compelling means of integrating this type of direct political dimension into the piece alongside the more poetic, philosophical elements that draw on duration and cultural/collective memory as a key element. I’d also mention Zoe Leonard’s, Survey, currently on view at The Whitney in New York as another highlight. The subtlety with which Leonard interrogates forms of representation and, like Bruguera, joins the personal with the political is really wonderfully seen within this particular grouping of her work.

Conditions for an Unfinished Work of Mourning: Beauty as An Appeal to Join the Majority of Those Who Are Dead. 2018 Faculty Biennial, The Cornell Fine Arts Museum at Rollins College, Winter Park, FL

Is there anything new and exciting in the pipeline you would like to tell us about?

Absolutely! I’ve installed various works from the current project mentioned above in a few different iterations recently (The Cornell Fine Arts Museum at Rollins College in Winter Park, FL; The Orlando Science Center, Orlando, FL; and Tracey Morgan Gallery, Asheville NC) and this summer I’ll have the opportunity to continue working on this project in a collaborative exhibition with my friend and colleague Leigh-Ann Pahapill. This 2-person exhibition, essay, v., will be installed at RAMP Gallery for Revolve Studio in Asheville, NC in August.

I will also have a satellite exhibition including components from this work at Tracey Morgan Gallery in Asheville, NC at the same time. I’ll also be traveling back to Portland this summer to go into a recording studio with a group of musician friends to begin generating audio for a soundtrack to be produced for a new video project connecting with the Pacific Yew Tree, its poisonous attributes, and its mythology as The Tree of The Dead. We’re going in with the intention of producing something brutal, and very loud. This is both a new approach for me, while at the same time somewhat of a return. We’ll see how it goes…

All images courtesy of the artist

Publish date: 30/5/18